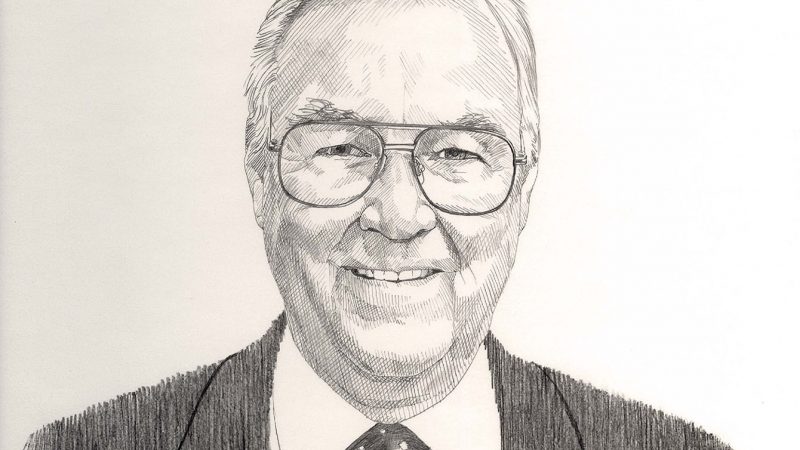

Col. W. Tandy Barrett

- October 4th, 2021

Some people are born leaders. Col. William Tandy Barrett was one of those. He was a military leader, a leader in the laundry business, and a civic leader.

Barrett was born in Russellville, Alabama, in 1901 and moved to Tuscaloosa in 1915. During his high school years, he was an all-around athlete and as a senior, he was captain of the football team. He graduated from Tuscaloosa High School in 1919 and entered The University of Alabama to study business management.

He worked his way through college, graduating in I 924. Many years later he said, “Nobody knew me or saw me much. I held two jobs. I ran to work and I ran to class. I had to work for a living, and I found out then I could do it.” He often singled out Dean Lee Bidgood and Dr. H. H. Chapman, professor of business statistics, as men who made a difference in his life. In gratitude, he later established the Colonel W. Tandy Barrett Scholarship in the College of Commerce and Business Administration.

Colonel Barrett enlisted in the Alabama National Guard in 1923 at the age of 23. He received his commission in 1924 while training as a cadet in The University of Alabama ROTC program and advanced to the grade of captain by 1929, when he assumed command of Company D. He commanded the company for over 11 years, including its call to active duty in 1940. He was then assigned to the staff of the 3rd Battalion, 167th Infantry, in 1941; was selected as part of the cadre for the formation of the 84th Infantry Division in 1942, and then became commander of the 3rd Battalion of the 333rd Infantry Regiment. He was involved in the unit’s training and led it into action in Normandy and into the German heartland, where his battalion engaged the enemy from October 1944 to January

1945 including the Battle of the Bulge. Upon his return to Tuscaloosa, he rejoined the Alabama National Guard as executive officer of the !6th Infantry regiment. In 1950 he was promoted to colonel and transferred to the U.S. Army Reserve where he was assigned to the command and general staff college program from which he retired in 1960. In 1965, Colonel Barrett was presented the Gold Medal of Merit by the Veterans of Foreign Wars. In 1983, Colonel Barrett was presented the Alabama Distinguished Service Medal, the highest honor the State Military Department awards.

Before World War II, Barrett worked for Perry Creamery. In 1946, upon his return to Tuscaloosa, he and his good friend Ernest “Rainy” Collins converted the Northington General Hospital laundry into a commercial operation. The business grew into West Alabama’s largest laundry with eight outlets in Tuscaloosa and Northport. He was dedicated to his profession and served as a board member of the American Institute of Laundering, president of the Alabama Institute of Laundry and Dry Cleaning, and vice president of the Southern Laundry Association. He was a director of the Tuscaloosa Chamber of Commerce and president for two terms. He received the rare honor of being named the chamber’s Member of the Year in two consecutive years, 1977 and 1978. Colonel Barrett was chairman of the Tuscaloosa County Industrial Development Authority from 1974 to 1978 and also served as president of the Industrial Development Board of the city of Tuscaloosa. He was a member of the Tuscaloosa Housing Authority Board. He was past president of the Tuscaloosa Exchange Club, director emeritus of City National Bank of Tuscaloosa, and director of Central Bank of Tuscaloosa. He was a Mason, a Shriner, and a member of First Presbyterian Church. Barrett also served on the boards of various clubs and philanthropic organizations.

In addition to his civic activities, Colonel Barrett was an avid sportsman and served as secretary/treasurer of the Dollarhide Hunting and Fishing Club for 40 years. Colonel Barrett, who was married to the former Mattie Winn Nicholson of Centreville, passed away in 1992 at age 91.