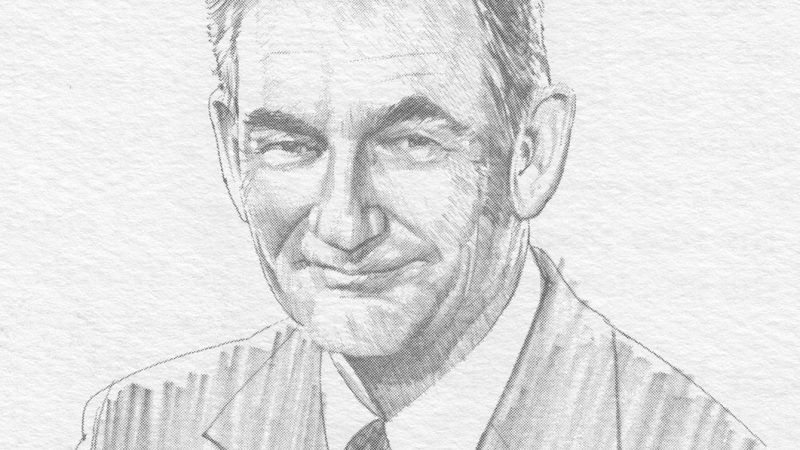

John Key McKinley

- September 20th, 2021

John Key McKinley, now Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Texaco Inc., has long exhibited qualities that seemed to forecast his rise to such a distinguished position.

He was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, on March 24, 1920, the son of Virgil Parks and Mary Emma (Key) McKinley. His father was a professor in the School of Education at The University of Alabama and his mother was a pioneer in providing kindergarten education in the University city. From his parents, he learned early the fascination of exploring the world of ideas and of working with people.

As a youngster in the Tuscaloosa public schools, he was known for his scholastic achievement and his enthusiastic participation in extracurricular activities. After graduating from Tuscaloosa High School in 1937, he entered The University of Alabama where he continued to excel as a scholar and leader. The extent of his scholastic achievement is apparent in his being named a member of both the chemical and engineering professional honor societies, and his wide participation and leadership in campus activities are evident in his being one of twenty-three in his class to be elected to Who’s Who.

John McKinley graduated from The University of Alabama with a B.S. degree in chemical engineering in 1940 and an M.S. degree in organic chemistry in 1941.

Immediately after receiving his M.S., Mr. McKinley joined Texaco on May 29, 1941, as a chemical engineer engaged in grease research at the Port Arthur refinery in Texas. Shortly the Army Artillery. For four and one-half years he wore thereafter, on August 15, 1941, he was called to active service as a reserve officer, with the rank of Second Lieutenant in the Army uniform, serving for three years in Newfoundland, England, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, rising to the rank of Major. He received the Bronze Star and various campaign medals in the European theater and was discharged from active service on December 25, 1945.

Returning to civilian life and Texaco employment, Mr. McKinley worked in Texaco’s research, processing, and development activities at Port Arthur. He was married there on July 19, 1946, to the former Helen Grace Heare. They have two sons, John Key McKinley, Jr., and Mark Charles McKinley.

At Port Arthur, Mr. McKinley was assigned again to grease research and then to cracking research, becoming Supervisor of that function in 1954. In 1956 he was transferred to the Company’s Central Research Laboratory at Beacon, N.Y., as Assistant to Management, and in 1957 became Assistant Director of Research. In 1960 he was named Manager of Commercial Development Processes. Later that year, Mr. McKinley transferred to Texaco’s New York City offices as General Manager-Worldwide Petrochemicals.

Always taking advantage of every opportunity to improve, Mr. McKinley attended the Advanced Management Program at Harvard University, graduating in 1962. He was elected Vice President in charge of the Petrochemical Department in 1967 and was named Vice President in charge of Supply and Distribution in 1970. In January 1971, he was elected Senior Vice President for Worldwide Refining, Petrochemicals, and Supply and Distribution. Mr. McKinley was elected President of Texaco Inc. and a Director of the company in April 1971.

He received honorary Doctor of Laws degrees from The University of Alabama in 1972 and from Troy State University in 1974.

In January 1980, Mr. McKinley was selected by the Board of Directors to be Chief Executive Officer on November 1, 1980, and was named Chief Operating Officer of the Company effective immediately. In June 1980, the Board of Directors elected Mr. McKinley to serve as Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer effective November 1, 1980. Mr. McKinley was elected Chairman of the Executive Committee effective July 1, 1980.

During his rise in the corporate structure of Texaco Inc., Mr. McKinley has always adhered to this business philosophy: “Business consists primarily of bringing together people, ideas, and capital to provide the necessary goods and services required by our society. An understanding of this basic fact is what makes it possible for those in charge of organizations to create a proper meld of these three elements, in appropriate proportion, to accomplish the stated goals and objectives.

“By and large, I believe that business and industry exist at the pleasure of the public. As long as the public perceives that the organization’s policies, programs, products, and services are in the public interest, that organization will be supported in the marketplace.”

Holding a number of patents in chemical and petroleum processing, Mr. McKinley, is a registered Professional Engineer and a member of a number of technical and professional organizations, including Tau Beta Pi, Sigma Xi, and The University of Alabama ( Capstone) Engineering Society. Mr. McKinley is a director of the American Petroleum Institute and a member of its Executive Committee and its Management Committee. He also is a member of the National Petroleum Council.

Mr. McKinley is a director of Burlington Industries, Inc., Merck and Company, Inc., and both Manufacturers Hanover Corporation and its principal subsidiary, Manufacturers Hanover Trust Company. He is a Fellow of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers, and Andrew Wellington Cordier Fellow of the School of International Affairs of Columbia University, a Sesquicentennial Honorary Professor at The University of Alabama, a trustee of the Council of the Americas, a director of the Americas Society and The Business Council of New York State, and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, The Conference Board, and the Business Committee for the Arts, Inc. He has been awarded the George Washington Honor Medal by the Freedoms Foundation.

Always a believer in both individual and corporate support of an art form, Mr. McKinley and Texaco Inc. have long been patrons of the Metropolitan Opera. On May 15, 1980, Mr. McKinley was elected a Managing Director of the Metropolitan Opera Association. At the same time, he was named national chairman of the Metropolitan Opera Centennial Fund. His other civic activities over the years have ranged from service on the advisory council of Reading Is Fundamental, Inc., to membership on the committee to determine the future of the new Westchester County (N.Y.) Medical Center Hospital. He is a former member of the Board of Governors of the Hugh O’Brian Youth Foundation.

In March 1981, Mr. McKinley was elected to the Board of Overseers of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, to the Board of Managers of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and the Board of Managers of Memorial Hospital for Cancer and Allied Diseases and the Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research.

Mr. McKinley’s hobbies include personally testing new developments m automotive engines, petroleum fuels, and electronic devices. His favorite sports are yachting, hunting, and golf. With his wide accomplishments and interests, John K. McKinley continues to be a man for all seasons.