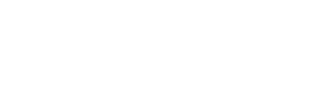

Samuel Paul Noble

- October 26th, 2021

Samuel Noble was the founder of Anniston, Alabama, which he envisioned as “the model city of the South.” He was an iron master and entrepreneur who helped Alabama’s recovery after the War Between the States by building this industrial base in Northeast Alabama.

The son of James and Jennifer (Ward) Noble, he was born in Cornwall, England, on November 22, 1834, but grew up in Reading, Pennsylvania, where his family had settled after emigrating in 1837. His father, an ironmaster, worked for a railroad until he could build a foundry.

Samuel Noble and his brother grew up in an atmosphere of furnace and forge. Young Samuel began learning his father’s craft at an early age by working in the foundry during school vacations. According to reports, he was always energetic. As a teenager, he was “full of both fun and work.” He belonged to the Reading Hose Fire Company, to a literary and debating group called the “Washington Club,” and a social dancing club. He also read law books and was interested in politics. During his years in Reading, Samuel Noble made many friends and contacts which proved useful to the family’s business in later years.

In 1855, when Samuel Noble was 21, the Nobles moved to Rome, Georgia, where they established James Noble and Sons. The Noble Ironworks soon became the largest of its kind south of the Tredegar Works in Richmond, Virginia. The enterprise included a foundry, rolling mill, nail factory, and stove and hollow wire factory, capable of making a variety of products

– from steam engines to boilers to iron bridges to mine equipment. One of the most famous products was the first railroad locomotive manufactured South of Richmond.

When the War Between the States began, the company obtained government contracts to produce iron products – such as cannons, cannon carriers, and caissons for the Confederate Army. The company experienced a setback when the uninsured carriage house and rifle factory in Rome were destroyed by fire, but about the same time obtained another government contract to build a new furnace. The result was Cornwall Furnace in Cherokee County, Alabama.

Samuel Noble took an active part in the Cornwall project, first as an overseer of the construction of the furnace and then as superintendent of its operation. He frequently made the 48-mile journey from the furnace site and back in one day – a strenuous trip in the 1860s.

Both the ironworks in Rome and the Cornwall Furnace were destroyed by Federal forces in 1864.

Samuel Noble had early emerged as the leader and spokesman of the family, perhaps because he was gifted with a hard, keen sense and practical energy. After the war, he secured capital from the North not only to rebuild the ironworks in Rome but also to buy extensive brownore properties and a large acreage of yellow pine for charcoal in Calhoun County, Alabama.

Samuel Noble traveled a great deal – raising capital or marketing the products of the Noble Iron Works. On a trip to Charleston, South Carolina, he met General Daniel Tyler, a capitalist from New York. Samuel Noble’s enthusiasm about the potential of the Alabama ore fields impressed General Tyler so much that he went with Noble to explore them. The result of this exploration was the formation of the Woodstock Iron Company in 1872, with General Tyler’s son Alfred as president and Samuel Noble as general manager.

By April 1873, the company had built and lit a forty-ton blast furnace (called No. 1 Furnace), and thus a new Alabama industry was born. The town of Anniston – named for General Tyler’s wife Annie – was established that same year.

No. 1 Furnace produced a high quality of carwheel iron which found a ready market in the North. The steady demand for this iron enabled the Woodstock Iron Company to survive the panic and depression of the 1870s. By 1879 the company was able to construct Furnace No. 2 and by 1880 to enlarge No. 1.

Anniston started in 1873 as a “company town” in a clearing in the woods – but not an ordinary one. Samuel Noble set out to make a model city. He laid out streets and parks. He provided lots for churches. He erected schools. The careful planning attracted wide attention.

In the 1880s Anniston grew by leaps and bounds, especially after 1883 when the Woodstock Company (which had retained possession of all property) formally opened the town to the public and encouraged new industries. Within fifteen years, Anniston had attracted over $11 million in capital investments.

Samuel Noble played a large part in the economic development of Anniston. He and his associates organized the Clifton Iron Company at Ironaton and built two 40-ton charcoal furnaces and also enlarged an older one called Jenifer. He acquired coal companies and constructed two 200-ton coke furnaces to make pig iron for the manufacture of cast iron pipe – a pioneer enterprise embodied in the Anniston Pipe Works Company organized in 1887. He was also instrumental in the construction of a cotton mill with 12,000 spindles.

Besides providing employment through industrial expansion, Samuel Noble enhanced community life by opening the Anniston Inn, which became a gathering place for both residents and visitors. He also launched the town’s first newspaper, The Hot Blast. He and General Tyler built the Grace Episcopal Church in Anniston.

Samuel Noble was known in the city he founded as a man who gave generously to every cause, race, and sect, and as one who earned the loyalty of his friends and employees. He was once described as a man who “put as much labor on his mental and physical forces in one hour as most men do in a year.”

Samuel Noble died suddenly on August 14, 1888, at age 53. This industrial pioneer had served Alabama well. He had established the foundations of a modern city and an industrial base in Northeast Alabama during the most difficult economic periods in the state’s history.

Source of biographical information: Grace Hooten Gates, The Model City of the New South: Anniston, Alabama, 1872 – 1900, Huntsville, AL: The Strode Publishers, Inc., 1978.