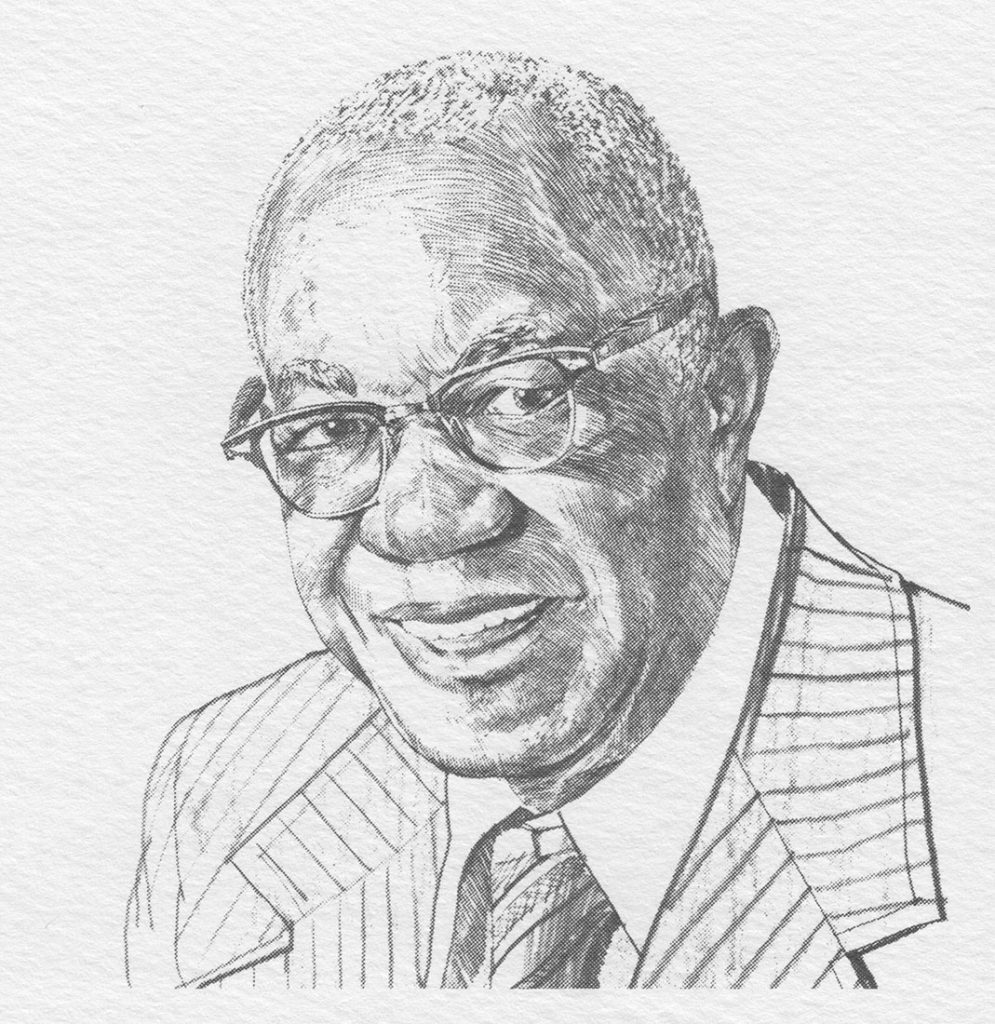

Eleven-year-old Arthur George Gaston believed in himself.

He was going to do something. He was going to be somebody. In some communities, such optimism might have been common in young boys his age, but in a poor, black community in turn-of-the-century Alabama, optimism about the future was an understandably rare commodity. Young Art Gaston, however, was a rare young man.

He was born in Demopolis, Alabama, on July 4, 1892. His father had died when young Gaston was only a few years old, and his mother had had to seek work in the city. Consequently, Art was reared by his grandparents, Joe and Idella Gaston, both of whom were former slaves. By farming and holding extra jobs with the white people in town, they had managed to buy a small farm and build with their own hands the log cabin in which their grandson was later born.

As self-reliant as his grandparents and as unafraid of hard work, eleven-year-old Art began his first business venture in his own back yard, charging neighborhood children a button each to ride on the old barn door swing that his grandfather had set up for him in a nearby oak. Business was unbelievably good, and before long Art had several cigar boxes full of buttons. He had also learned his first business lesson: find a need and fill it. He would remember that.

Later that year he moved to Birmingham where his mother, Rosie Gaston, now a cook for a wealthy white family in town, enrolled him in the Tuggle Institute, a school for black children in the hills of north-west Birmingham. Granny Tuggle, who had started the school in 1908, was a former slave who knew firsthand the difficulties her young charges would face if they were thrust into the world without a sense of responsibility and at least a rudimentary education. Granny liked Art Gaston and she worked him especially hard. During his years at the Institute, he learned to organize his time between his studies and the many odd jobs he picked up on the side. By the age of 18, he had completed the tenth grade and had learned from experience the difficult time blacks had finding anything but the most menial employment.

Determined to secure something better for himself, Gaston joined the Army. Already a seasoned soldier by the time the U.S. entered World War I, he served in France as a Regimental Supply Sergeant and was decorated with his entire unit for “valor beyond the call of duty.” Having served his country well, Gaston hoped, as did thousands of other returning Negro soldiers, that a grateful nation would offer them opportunities never available to blacks before. Disappointed to find that nothing had changed, the self-reliant Gaston supported himself as a laborer while he began to create opportunities of his own.

He noticed that the black community frequently collected donations at funerals to help pay burial expenses. Deciding that burial insurance would be both helpful to the community and profitable, he launched the Booker T. Washington Burial Society in 1923. It was a daring venture for a young man with little capital, but the idea was sound, and by the end of the year, the young entrepreneur had to hire additional agents to handle his burgeoning business.

With prospects for the future considerably brighter now, Gaston married his childhood sweetheart, Creola Smith, and asked his new father-in-law to join him in business. The partnership worked well, and before long the two were able to purchase a funeral home which they promptly renamed Smith and Gaston, Funeral Directors, Inc.

Then, in 1939 his father-in-law died, and within six months, so did Creola. Devastated by the loss of his family, Gaston devoted himself to his work in the years that followed. He listened attentively to the advice of other businessmen; he learned to digest a profit-and-loss statement and to keep a sharp eye out for sound investments. His sharp eye also landed on a young college graduate, Minnie Gardner, a particularly attractive and resourceful young lady who soon became his wife. Minnie turned out to be one of Gaston’s greatest assets.

From the beginning, Gaston’s businesses had suffered from his inability to find well-trained Negro clerical staff. To solve his own problems and to help his community at the same time, he started the Booker T. Washington Business College. Minnie took over the College’s management and under her guidance, the school grew faster than either the insurance company or the funeral home had in their infant years.

The pattern of Gaston’s success continued. By helping himself he had helped his community, and he felt an obligation to pass on what he had learned. “Study as hard as you can, save a part of everything you earn, and contribute to your community to the limit of your ability,” he told civics classes, church groups, anyone who would listen. ”The world does not owe you a living, only the chance to earn a living based on your merit.”

Gaston followed his own advice. The black community lacked first-class motels, restaurants, nursing homes, and pharmacies, so over the years, he built these and more. He founded a savings and loan association, a realty and investment corporation, a broadcasting company (WENN Radio), a fire insurance company, and he built a 1.5 million dollar building in Birmingham to house his enterprises. He served on the board of more than twenty-five local, state, and national civic organizations, and he founded and supported the A.G. Gaston Boys’ Club.

Respected by both black and white communities in Birmingham, Gaston was turned to repeatedly for leadership during the civil rights riots of the 1960s. Although his home was burned and his motel bombed, he remained a voice of reason. He appealed to all the citizens of Birmingham to “live together in human dignity as American citizens and sons of God.” Ironically, his moderate stand angered radical blacks, who wanted to expand the disorder, and conservative whites, who criticized him for providing financial assistance to civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr., for whom Gaston had provided bail.

His sound leadership did not escape the attention of President John F. Kennedy, however, invited him to the White House for a state dinner. Nor have his contributions and achievements escaped the attention of many others. Gaston is a member of the Alabama Academy of Honor, the recipient of honorary doctorates from nine institutions in this country and abroad, including one from The University of Alabama; and “A.G. Gaston Appreciation Days” have been celebrated by Demopolis, Brighton, Birmingham, and Jefferson County.

The trip from a Demopolis farm to one of the leading citizens of Alabama was a long one, but A. G. Gaston more than realized his childhood dream. Overcoming poverty, prejudice, and limited education, he amassed corporate holdings in excess of thirty-five million dollars, and, along the way, he improved his community and the lives of the people in it, both black and white. His method was simple: He believed in himself, he believed in God, and he believed, as did George Washington Carver, in “the great human law, which is universal and eternal, that merit, no matter under what skin found, is in the long run, recognized and rewarded.”