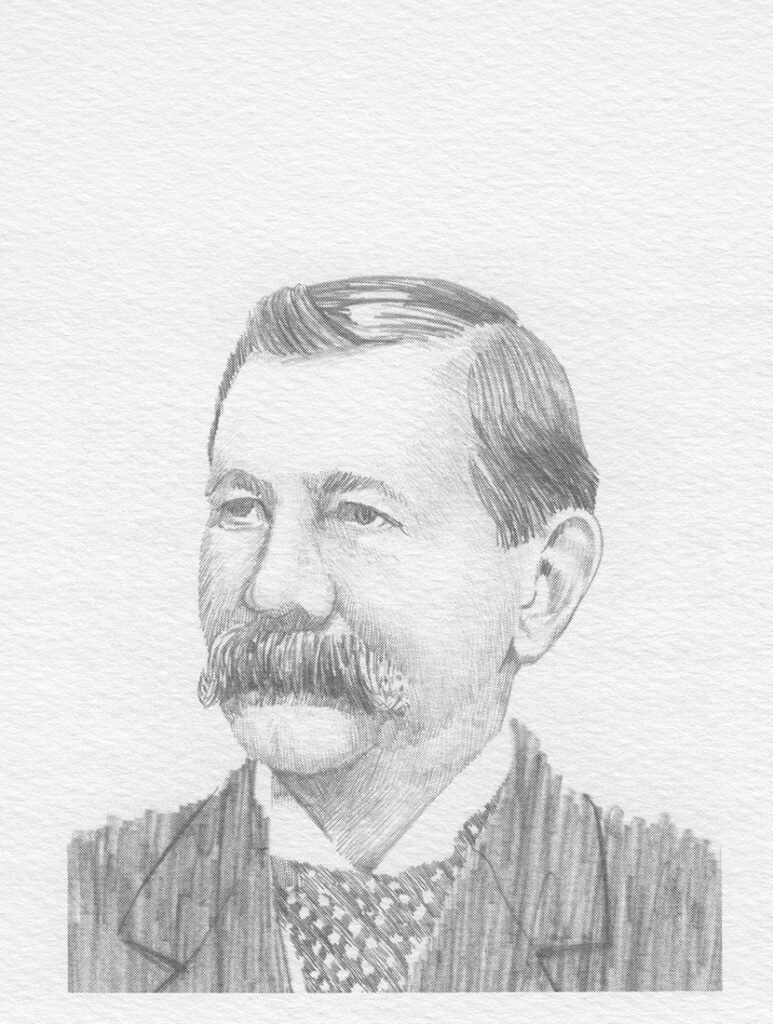

Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben once said, according to historians, “Break a young mustang into a foxtrotting gait. That’s what we did to the Birmingham district.

“There’s nothing like taking a wild piece of land, all rock and woods, ground not fit to feed a goat on, and tum it into a settlement of men and women, making payrolls, bringing the railroads in, and starting things going …

‘That’s what money does, and that’s what money’s for. I like to use money as I use a horse – to ride!”

And “ride” he did. He put the power of his fortune, his credit, and his tremendous vitality into the development of Birmingham as the “Pittsburgh of the South.”

Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben was born in Autauga County, Alabama, on July 22, 1840. His father Henry died when the boy was twelve years old. His mother, Mary Ann (Fairchild) DeBardeleben, subsequently moved to Montgomery where the youngster secured work in a grocery store. Being a native of New York, Mrs. DeBardeleben sought the company of others from that area. The Daniel Pratts, whom she had known in New York, became benefactors of the widow and her three young children.

When young DeBardeleben was sixteen, he became the ward of Daniel Pratt, Alabama’s first great industrial magnate, whose plants were in Prattville, a few miles from Montgomery. The young man lived in the Pratt mansion and attended school. He was made ”boss” of the teamsters and foreman of the lumberyard, and later superintendent of the cotton gin. Upon the outbreak of the War Between the States, he joined the Prattville Dragoons in the Confederate Army. He served until after the Battle of Shiloh when he was detailed to take care of a Prattville grist mill and bobbin factory which supplied food and clothing to the Confederate Army.

In 1863 he had married Ellen Pratt. After the war, he continued to run the Prattville mills for his father-in-law. In 1872, Daniel Pratt bought a controlling interest in the Red Mountain Iron & Coal Company in Birmingham and made Henry DeBardeleben manager of the reconstruction of the Oxmoor furnace and the development of the Helena mines. The panic of 1873 temporarily closed the works. This same year, Daniel Pratt died, leaving his estate to the Henry DeBardelebens.

In 1877, Henry DeBardeleben joined James W. Sloss and Truman H. Aldrich in ownership of the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company, which was reorganized in 1878 as the Pratt Coal and Coke Company with DeBardeleben as president. Two years later, he and T. T. Hillman founded the Alice Furnace Company, and between 1879-81 built the Alice furnaces, named in honor of DeBardeleben’s eldest daughter.

In 1881, because of ill health, he sold his holdings and took his family to Mexico. But by 1882, apparently fully recovered, he returned to Birmingham and with W. T. Underwood built the Mary Pratt furnace (named for his second daughter). He acquired the mineral rights to a tract of land on Red Mountain. Illness again took him from Birmingham, this time to Texas, but by 1885 he was back in Birmingham. In 1886, he and David Roberts, whom he met in Texas, formed the DeBardeleben Coal & Iron Company (apparently, whenever he traveled away from home, he could, through his personality, persuade men of means and enterprise to follow him to Birmingham). He also organized the Pinckard-DeBardeleben Land Company.

These interests led to the founding of the town of Bessemer, ten miles west of Birmingham, and near the great Red Mountain iron seam. In Bessemer, named for the British inventor of the Bessemer process of steelmaking, four furnaces and an iron mill were erected. In 1887 these two firms merged into the DeBardeleben Coal & Iron Co.

In 1891, the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company took over controlling interest in the company. DeBardeleben was made vice-president. After three years of virtual retirement in this position and the death of his wife, DeBardeleben was so restless that he went to New York and made an attempt to gain control of the company through stock purchases. He lost his entire fortune.

Indomitable in the face of ill fortune, he, with his sons, Henry and Charles, explored new fields and started mining in St. Clair County, Alabama, and in the Acton Basin southeast of Birmingham.

In 1910. What had he accomplished in his lifetime? His Red Mountain seam, with his Pratt coal seam, was the basis for the development of industrial Birmingham. He was the first to succeed in making pig iron in Birmingham cheaper than it could be made elsewhere. He built the first coal road in Alabama and aided T. H. Aldrich in exploring and developing the Montevallo coal fields. He contributed to the development of his region not only through the enterprises with which he was directly connected but also by attracting to Birmingham moneyed men of ambition who established other enterprises. He talked of making steel long before it was made in the Birmingham district, and was instrumental in the construction of the first rolling mill and furnaces.

In 1905, Col. L. W. Johns said he would pay off the Vulcan statue account provided the statue be erected in honor of Henry F. DeBardeleben. DeBardeleben declined the honor-one of the greatest honors proposed to a living personbecause he felt such a monument to the industrial pioneer movement should perpetuate the character and achievement, not of one individual, but of all of the men in the past and present who led or were leaders in the industrial development of the Birmingham district. He would prefer, he said, a living, breathing monument that would be a fountain of wise charity. He proposed the establishment of a trust fund to be used for the hospital treatment of the poor and needy.

Thus, it can be said that Henry F. DeBardeleben was not just an industrial giant who fostered industrial growth in Alabama. He was also a man who exhibited the traits of those who believe that “every man should leave this world a better place for having lived in it.”