Energetic, independent, and adventurous, he was the inheritor of a pioneering spirit that had characterized the Jemison family for generations.

His great-grandparents had immigrated to the colonies in 1742, settling on a farm in Pennsylvania; his grandparents had moved to Augusta, Georgia, sometime before the start of the Revolutionary War; and his parents, prosperous Georgia landowners, sought out the rich farmlands of West Alabama and built there a plantation so productive and well-cultivated that it came to be known as The Garden.

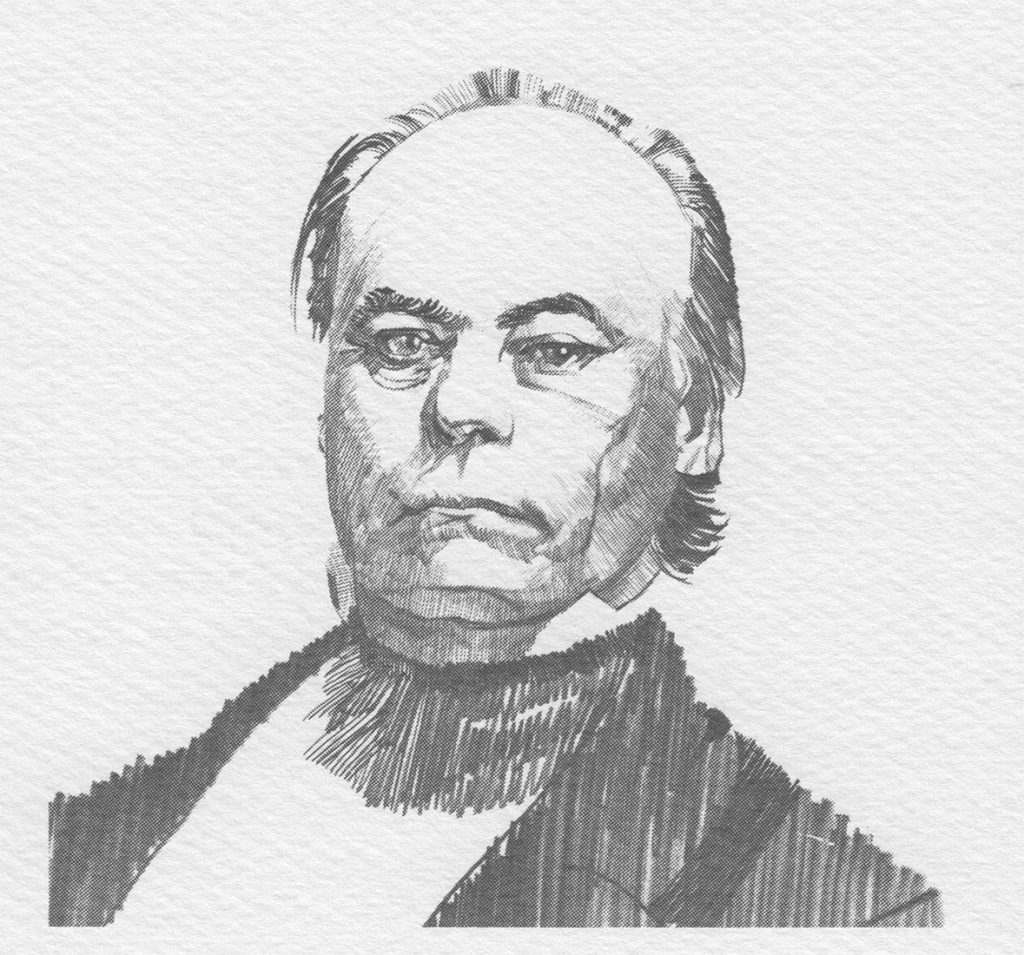

It was near Augusta, Georgia, in 1802 that Robert Jemison, Jr.* was born. He attended the University of Georgia, read law, and in 1821 moved with his parents, William and Sarah Jemison, to Alabama. The family settled briefly in Greene County and then moved to the village of Tuscaloosa. In 1826 the elder Jemison transported his family to Pickens County where he founded and developed his prosperous plantation, The Garden, and helped finance blacksmith shops, lumber mills, and other services for the community.

Robert Jemison, Jr., who lived and worked at The Garden for ten years, returned to Tuscaloosa in 1836 and married Priscilla Taylor of Mobile. They had one child; a daughter named Cherokee. Jemison and his wife were said to be particularly fond of that Indian name because the story goes, several generations back the Cherokees had done a favor for the Taylor family and requested, in return, that the family perpetuate their name. Jemison more than complied with his wife’s ancestor al obligation by giving the name, not only to his daughter but to the large plantation he built beyond Northport.

Like his father before him, Robert Jemison was an enterprising businessman. In the 1820s he began to buy up small tracts of property in several counties. As the size of his holdings grew, he added buildings, improved the efficiency of his farming operations, and added grist and flour mills. By 1857, he owned six plantations, the largest of which was the 4000-acre Cherokee Place.

Industrial and commercial enterprises also interested him. He invested heavily in stagecoach lines, operated a large livery stable in Tuscaloosa, and built a thriving lumber and sawmill business. He erected a foundry in Talladega County, operated several surface coal mines near Brookwood, and constructed a plank road from the mines to Tuscaloosa. The lumber for all his enterprises, as well as for his several homes, came from his own mills; the labor, from his slaves – estimated to total nearly 500 at one point. Not surprisingly, Jemison was considered “the most enterprising all-around citizen in Tuscaloosa.”

It was as a statesman, however, that the people of Alabama knew him best. He first entered politics in the mid-1830s by filling a vacancy in the state legislature, then located in Tuscaloosa. In 1837 he ran on the Whig ticket for that same legislative post and won. For the next twenty-five years, he continued to win elections, serving in the statehouse of representatives until 1850 and in the state senate from 1851 to 1863. During his long political career, Jemison gained a reputation as a skilled debater who would speak his mind regardless of the unpopularity of his view. “The duty of a statesman,” Jemison reportedly said, “is to lead and not to follow popular sentiment. If he finds public opinion taking the wrong direction, it is his duty to throw himself in the breach and turn it the right way.”

Jemison frequently threw himself into the breach. He was a determined supporter of a system of railroads for Alabama, an active anti-abolitionist, and he fought tenaciously – and successfully – for the construction of a state hospital for the insane (Bryce). It was in 1847, though, that he took on what may have been the most challenging problem of his career – the failing financial affairs of the state of Alabama.

Jemison had long opposed the system of state banks. ‘This hydra of modern banking,” as he called it, had led to wild speculation schemes, to the panic of 1837, the failure of the banks, and to public debt that by 1847 had reached crisis proportions. Chosen by his constituents and the legislature to lead the state out of its financial mire, Jemison advocated the liquidation of state banks and the establishment of a well-regulated system of private stock banks. He was convinced that Alabama, by reason of her abundant resources, was amply able to pay her debts, and he dismissed arguments that a tax bill commensurate with the wants of the state would be disastrously unpopular. As chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, he introduced a revenue bill that, once passed, revolutionized the state’s system of taxation by establishing a broader and more equitable distribution of the tax burden. Even Jemison’s staunchest political adversaries applauded his skill in introducing sound business practices to the management of the state’s financial affairs.

In January of 1861, Jemison once again attempted to influence the direction of his state, but this time he was not successful. Representing Tuscaloosa County in the Secession Convention in Montgomery, Jemison argued against seceding from the Union. Such drastic action was premature and impractical, he reasoned; the Convention possessed no reliable evidence to suggest that the North planned to invade the South; the matter deserved careful consideration; perhaps there was still room for compromise. Amid the Convention’s emotional atmosphere, Jemison’s efforts to discuss the issue on practical grounds proved ultimately futile. Once the Ordinance of Secession passed, however, he stood behind the majority opinion and supported the Confederacy with all the resources at his disposal.

In 1863 he was chosen president of the state senate, and that same year he was elected by an overwhelming margin to succeed the late W. L. Yancey in the Senate of the Confederate States of America. There he served actively until the fall of the Confederacy.

Senator Jemison was in Tuscaloosa in April of 1865 when Federal troops invaded the city and burned factories and mills and The University of Alabama. He escaped imprisonment by hiding in a swamp outside of town while soldiers searched his home, a large Italianate villa that still stands on Greensboro Avenue.

After the war, with most of his property destroyed, Jemison remained in Tuscaloosa and began to piece together the remnants of what had once been a vast system of enterprises. Although his health was failing, he built a ferry service across the Black Warrior River and devoted much of his time to the work of rebuilding The University of Alabama.

When he died following a long illness on October 17, 1871, the citizens of Tuscaloosa and Northport closed their shops and businesses and turned out en masse for his funeral. It was but one of many tributes paid throughout the state to Robert Jemison, Jr. – a man whose statesmanship, business acumen, and pioneering spirit had contributed to the development of the nineteenth century – Alabama to a degree that few of his generation could match.