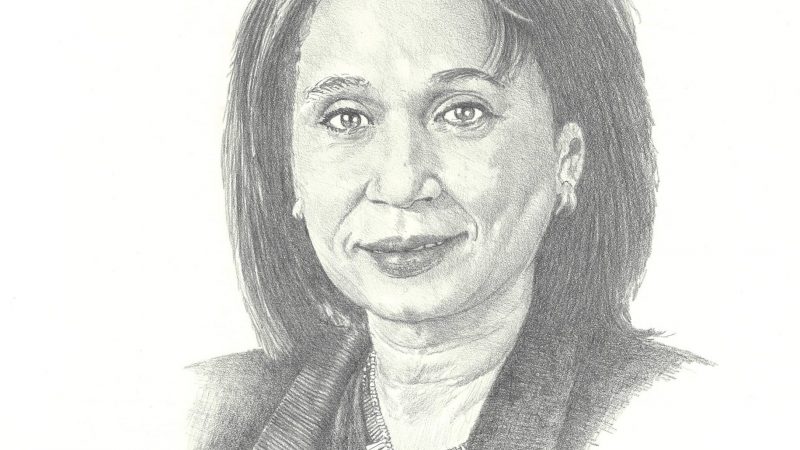

Alfred Saliba’s favorite quote in large measure describes the life he has led. The quote is from Leo C. Rosten, the Polish-born American humorist-sociologist:

I cannot believe that the purpose of life is to be happy. I think the purpose of life is to be useful, to be responsible, to be honorable, to be compassionate. It is, above all, to matter; to count, to stand for something, to have made some difference that you lived at all.

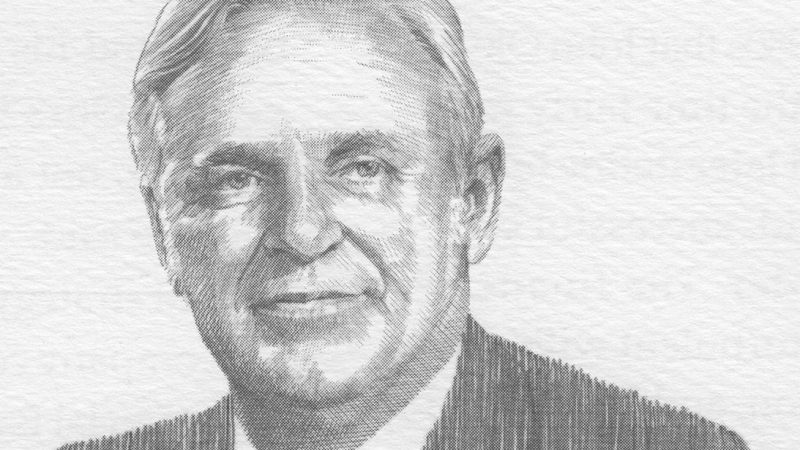

No wonder, then, that Alfred Saliba, businessman, builder, and former Mayor of Dothan, has spent his life being useful, responsible, honorable and compassionate, making sure that he stands for something, that his actions matter, that he has made a difference to those around him and to his community.

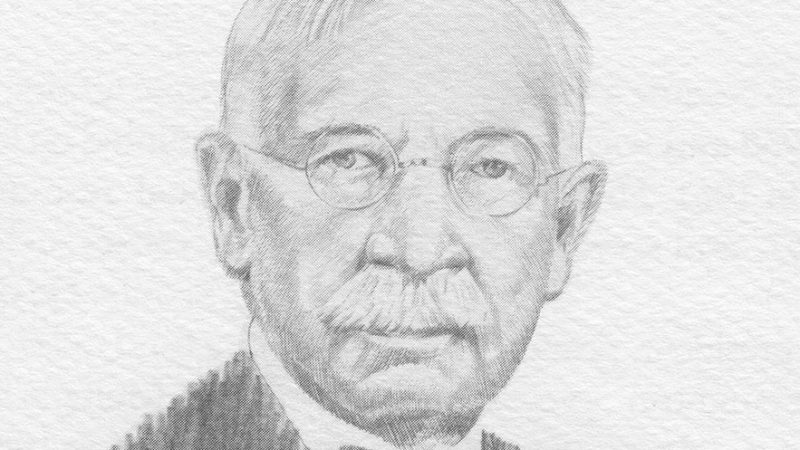

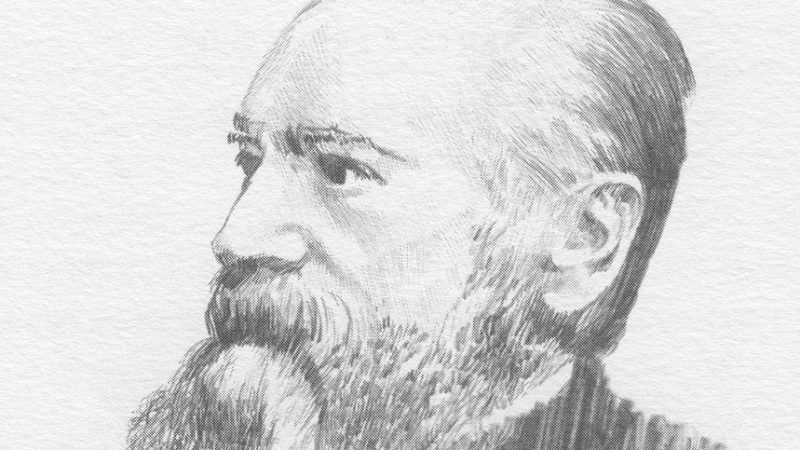

Born February 22, 1930, to Joseph Elias Saliba and Marie Violet Accawie in Dothan, Alabama, Alfred Joseph Saliba comes from roots that reach deep into Dothan history. Lebanese immigrant Elias Thomas Saliba began a one-mule trade business while visiting friends in nearby Ozark. Hotel owner and Dothan Mayor Buck Baker struck up a friendship with the young man and loaned him a building rent-free. After building his own wholesale grocery and tobacco business, Saliba sent for his younger brothers, Mike, Mose, and Abe, and set them up in business, selling groceries and running restaurants. The family patriarch returned home to Lebanon to visit, and while detained by World War I, he was elected mayor of his hometown. He was assassinated and the family returned to Dothan, where decades later his grandson would be elected mayor.

As a youth growing up in the Wiregrass, Alfred Saliba demonstrated quiet intelligence, high ethic caliber, and fair-minded commitment to justice, and a sincere understanding of people that combine to create fine leaders.

His organizational skills and inspirational leadership became apparent while in grade school. They were raised to the level of fine art at Dothan High School and became legendary at The University of Alabama, where he earned a degree in civil engineering/construction. His willingness to work hard and his ability to improvise were tested when he was misinformed about qualifying dates and missed placing his name on the ballot for the presidency of the College of Engineering at UA. He immediately sent handwritten notes to every engineering student, including the other candidate, explaining the error, assuring them of his desire for the position, and seeking their support. He won as a write-in.

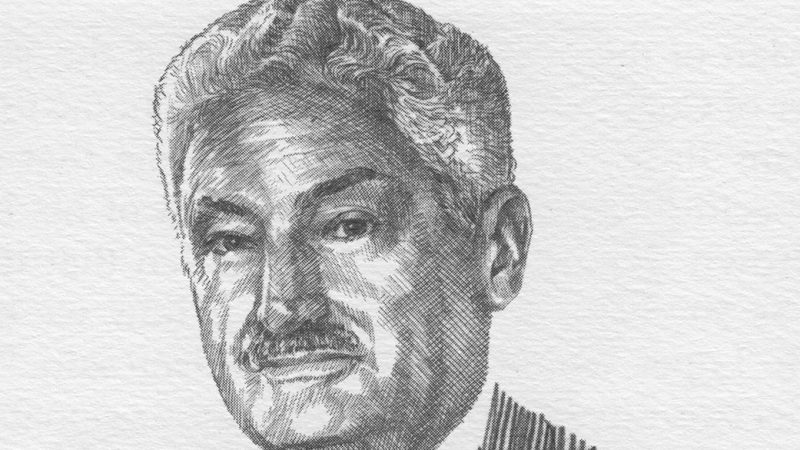

In 1953, Alfred Saliba entered the U.S. Air Force as a 2nd Lieutenant, having been a member of the Arnold Air Society, the Pershing Rifles Honor Guard, and both a Distinguished Military Student and Distinguished Military Graduate at the University. He was released as a First Lieutenant after service in Japan and Korea and earning the UN Service Medal, Korean Service Medal, and National Defense Service Medal. He achieved the rank of Captain in the Air Force Retired Reserve.

Alfred Saliba is renowned for his tendency toward careful thought, consideration, discussion, and contemplation. No quick decisions. Except when it comes to matters of the heart.

When he returned home after his duty in Asia, he planned a visit to his younger sister at the University. It was April 1955, the annual A-Day event, and sister Norma scrambled to find her brother a date. Most people already had plans, so she begged her roommate, Henrietta Carpenter, to go out with Alfred as a favor. He proposed the next month and the couple was married on August 20, with sister Norma as a bridesmaid. The union produced three children, Annamarie Saliba Martin, Alfred Joseph Saliba Jr., and James Mark Saliba.

In 1955, Alfred Saliba set about earning a living in Dothan. He established his own home building, land development, and residential/commercial real estate firm. His professional standards and personal integrity provided a solid foundation for the business and, as founder and president, his hard work ensured the success of the Alfred Saliba Corporation. In addition, he is a shareholder or on the board of directors of Houston Properties, Inc., Wasco Properties, Southeastern Apparel, SMK (Ethan Allen, Dothan, and Birmingham), SMW (The Playground), Dothan Inn, Inc., PENTA, Inc., and Regions Bank-Dothan.

Saliba has been instrumental in boosting the growing business community and economy of the Wiregrass area. He was a founding partner in Aladan which quickly became the largest U.S. manufacturer of latex products and Columbia Yeast Company which became the largest American producer of yeast. He also helped engender Behavioral Health Systems, one of the Southeast’s leading providers of corporate mental health management care.

As diverse and impressive as his business career is, his community and civic service may eclipse it. He has been president of the JayCees, Rotary Club of Dothan, Dothan Chamber of Commerce, and the Hawk-Houston Boys Club. He has been active in the Republican Party, serving as Chairman of the Houston County Republican Executive Committee and as a member of the State Executive Committee. Through service as an elder at Evergreen Presbyterian Church, he helped establish the area’s first senior citizen hot lunch and day program and the city’s first church-sponsored kindergarten/daycare.

He has served on the board of directors of the Salvation Army, Wiregrass United Way, Wiregrass Habitat for Humanity, Community Foundation of Southeast Alabama, and the Industrial Development Board.

His community service has brought him numerous honors: JayCee Boss of the Year, Builder of the Year, NASW Public Citizen of the Year, the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award, the Arthritis Humanitarian Award, and the Troy State University Dothan Community Service Award. He was tapped for Leadership Alabama, and former Gov. Fob James proclaimed November 21, 1997, as” Alfred Saliba Day.”

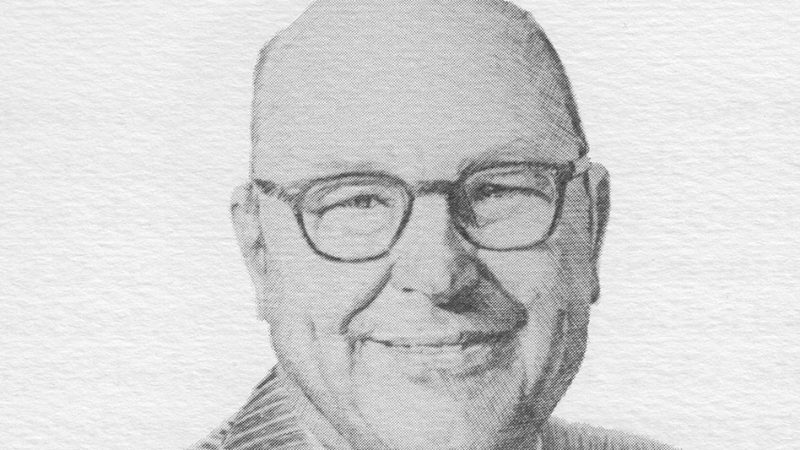

Given his record of business success and public service and his personal connection to Dothan’s history, it seemed natural that Alfred Joseph Saliba should follow the example of his grandfather, Elias Thomas Saliba, who had been elected mayor of his hometown long ago in Lebanon. At the urging of several friends, and without a shred of experience as a political candidate, Alfred Saliba ran for mayor of Dothan and won.

Through two, four-year terms he used the wisdom of a lifetime of business acumen to bring foresight, managerial expertise, diplomacy, and fiscal responsibility to the office.

He developed a long-range plan for revitalizing the infrastructure of a growing Dothan and initiated a comprehensive plan for funding needed capital improvements. For three consecutive years of his second term, Dothan was selected by Money magazine as the best place in Alabama to live, ranking as high as 39th in the nation for quality of life.

In 1993, Mayor Saliba formed a task force to assess community needs, seeking an alternative to welfare for Dothan’s struggling families. The task force reported gaps in community services, lack of adult education in living/working skills, and fragmented delivery of services, which often resulted in multigenerational dependence on welfare. Emboldened by Saliba’s vision, the task forces brought together health and service organizations to co-exist and cooperate in one central location.

The result, which bears the name Alfred J. Saliba Family Services Center, was a prototype in the state. Its complement of agencies and innovative programs has aided and uplifted hundreds of impoverished families and has been declared a model for welfare to work, inspiring 15 other Southern cities to follow suit.

Newspapers are not usually given to applauding politicians. Yet The Dothan Eagle, in an editorial praising the oratorical prowess of Mayor Saliba, said: “We still remember the brief talk he gave before a group of veterans in the Civic Center on Memorial Day morning. Anybody in that audience who did not feel chills along his spine or who left not feeling proud to be an American was listening to another drummer.”

In an article in that same newspaper, Mayor Saliba, writing in a guest column, referred to his grandfather. ” … His vision and love for this small corner of the New World inspire me even today.” And, in a life of achievement, service, leadership, and compassion, Alfred Saliba shares his own vision and love for Dothan, inspiring present and future generations.